MORE ARTICLES, PUBLICATIONS, DOCUMENTS

Scratched, battered, mottled and sometimes blurred, most of the Saul Levine films showing in the Views From the Avant-Garde series, as part of the New York Film Festival, look as if the artist had dragged them across cement before sharing them with the world. The films have been gathered together in the program “Saul Levine: Notes From the Underground,” a title that plays on twinned ideas: the underlying sense of protest and subversion that animates the work, as well as its historic, symbolic and sometimes even physical place in the larger culture. These are films that proudly sing the subterranean blues.

The program includes four films shot over a number of years, beginning in the late 1960’s; the fifth, “Note to Poli,” dates from the early 1980’s. All are silent and short, and were shot on eight-millimeter film, a small-gauge film stock introduced for the home market by Kodak in 1932 and appropriated by artists for many of the same reasons that would have appealed to your grandparents: its relatively inexpensive price, its accessibility and its ease of use. The film frame might have strained the eye when it came time to edit (one frame is about as big as a child’s fingernail), but the small size and light weight of the cameras was liberating and put the tools of production directly into the hands of the artists.

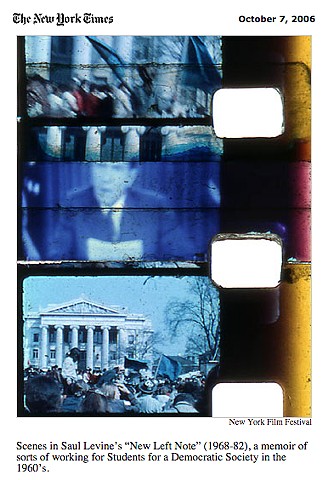

The longest Levine film here, at 26 minutes, “New Left Note” (1968-82), opens with the printed words “Less talk more action” and the image of a clenched fist. Mr. Levine was the editor of the radical student newspaper New Left Notes, the national paper of the Students for a Democratic Society, when he shot these images (the date 1982 refers to when he went back to edit), and you feel the urgency of the era pulsing through them from start to finish. With stuttering, lurching rhythms and a hand-held camera, Mr. Levine rushes from one tableau to the next — Richard M. Nixon talking on television; people massed in the streets, raising fists and political placards — as if there were something at stake, and there was.

Among Mr. Levine’s most striking strategies is to turn the plastic editing tape that holds or splices the images together into an aesthetic gesture. Commercial film editing is usually meant to go unnoticed, to serve an illusion of seamlessness that in turn serves the narrative. In this work the bubbled and ragged bits of editing tape, which look very much like scraps of hastily applied cellophane, contribute to the artisanal aspect of the individual shots and the work as a whole, as well as its maker’s outsider status. You feel his presence, his body and emotional engagement, in each jagged edit and tremulous shake of the camera: this is truly handmade art, created outside the realm of industrial film production.